I've started this blog post not knowing too much about the former popular method of heating with coal, and I'm still not going to pretend I know a lot, but the information I included below is the most interesting I've been able to learn. And it ends with a blackened lung in a jar. Now I've piqued your interest, I bet.

In case you're like me, and enjoy learning about the ins and outs of behind-the-scenes operations keeping us alive and well, then you'll hopefully enjoy this blog post. In this case, I'm specifically talking about heating in a home or building. Today, we're mostly used to electric, gas, or even propane (and anything else I'm missing), but that's not always been the case and in fact, there used to be more evidence left behind thanks to the method of heating coal around the end of the 19th century into the mid-20th century.

We're familiar with it in Archives because several of the older books in our collections are still covered with the residue from the coal. So when processing and preserving a book or collection, we have methods we use to help remove some of the coal dust from the book.

Or here's another example of heating with coal. Have you seen the movie "A Christmas Story"? Most of you reading this just said "uh duh, of course I have." Well, remember the scene when "the old man" goes into their basement to fix the furnace (more like fight with it), while the mother went into the living room to "water her plant"? Well, "the old man" comes running back upstairs when he hears the lamp break, covered in black soot - that was coal dust.

But in case you're interested in learning a little bit more about the history of coal heating, and how it impacted daily lives, please read on...

The Messy Method of Heating with Coal

Prior to heating with coal, a regular method of heating a home or building was often with wood. During the colonial era and most of the 19th century, wood was the product used for burning since there was an abundance of it. Of course, this is still a method of heating today but it's mostly not the primary source of heating in people's homes, emphasis on mostly there; obviously there are scenarios such as camping outside that a wood-burning fire is your primary source of heat.

One news article I read from 2017 called "Beyond Fireplaces: Historic heating methods of the 19th century" elaborated on just how fireplaces changed throughout the 19th century. I won't dig too deep into what the article says, but it's important to note that part of the issue with the earliest fireplaces was that it was difficult to keep the heat inside the room as opposed to it traveling up and out of the flue. Various other methods were invented, including one by Benjamin Franklin that wasn't fully successful, but that's where we transition to the use of coal for heating.

According to the U.S. Dept. of Energy's website, coal was easier to burn than wood because it can burn longer (and therefore didn't need to be collected as often as wood).

While coal was primarily used for heating during the early to mid-20th century, as early as the 1820's saw coal being transported across the ocean to major American cities. But because of this expense, it was mostly only used in larger buildings and wealthier homes. It took the use of coal some time to become popular in the United States as well, and actually took off more after the Civil War. When it did, wealthier families may have burned their coal in basement furnaces while less-affluent families would have used smaller stoves in individual rooms of their homes.

Also when it took off, it became the most abundant fuel most widely used and that's not just for heating, but also for industrial processes as well, such as powering trains or ships. Again, I reference a movie...

Ever heard of a little movie called "Titanic"? Yeah, it wasn't that popular. Anyway, if you have seen it, you'll remember the scene when Jack and Rose were running through the lower decks, near the firemen shoveling coal into the furnaces. There you go, another historic example of coal usage. Or check out the image below too from a train powered by coal.

Similar to today's fireplaces that are converted to gas-burning, coal was also retrofitted into wood-burning fireplaces. Or more popular were the stoves that could burn either wood or "hard" coal (also known as "Anthracite" - more on that below).

Or if you were lucky (and wealthy), you could get a coal stove with decorative and intricate ironwork to accompany its usefulness.

What did the introduction of coal stoves mean for the architecture of a home? Instead of bigger chimneys that were needed to support multiple fireplaces, skinnier chimneys were now a thing of the later 19th century since ventilation space for stove pipes were all that was needed. Evidence of this change in architecture can most likely still be found in many older homes today. Some homes may even still have their boilers or furnaces, converted into fuel oil or gas. Many basements still have their coal bins as well.

Ventilation brings up one more thing that's discussed in that same article about historic heating methods. It also prompts recommending another read, because that's the source of this next information...

Steam Heating was another form of heating that became most popular in the 1880's. But it's also a form of heating with coal, since that's what was used to heat the water that turned into steam. One of the best examples of a steam-heating network in a residence from the 19th century - the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina. Here comes the book recommendation if you'd like to learn more about this massive network of boilers, radiators, shafts, and plenty of coal to keep the "175,000-square-foot-house" heated...

- From a different blog post about the history of coal heating, the writer points out that it was actually as a result of World War I creating a shortage of the fossil fuel that caused its peak in 1920. Though at least in Nashville, it continued to be used up until the 1950's.

- From the same blog, the writer points out that fuel oil burners became a safe and reliable source of heating by the 1930's (though it wasn't as popular in Nashville).

- And lastly, I suspect it's just like why coal replaced wood-burning for heat - a better, cheaper, cleaner, and potentially safer means of heating was discovered. People no longer needed to buy coal in bulk to have stocked up for the winter time, and no longer needed to constantly clean their surfaces of coal dust when the cleaner, cheaper, and safer means of electric heating came along.

- Am I missing anything? Please comment below if you'd like to add something I didn't mention.

Smoke Abatement Reports from the Board of Public Works

Following in the steps of several other cities (namely Chicago's ordinance since that's what Nashville modeled their initial ordinance after), 1912 appears to be the first year that Nashville attempted to do something about the "smoke nuisance" that was ever growing in Nashville thanks to the burning of coal.

The collection of the Smoke Abatement Commission that we have in Archives only covers the years of 1925-1929, but from doing some digging through newspapers and government-related records, I've been able to trace a little more history about the Commission's creation and effect.

According to the 1913 article of the attached heading, the creation of the commission was due to:

"...the smoke conditions in the city, however, have been constantly growing worse, due to the increase in the size of Nashville and the multiplication of factories, hotels, office buildings, and other concerns producing large amounts of smoke"

But based on seeing many photos of downtown Nashville during the 1940's and 50's, where the city looked like it was completely covered in soot, the commission wasn't going to be a one and done thing. In fact, that same 1913 news article concluded with the statement that "this work is one that will take time to accomplish and, in fact, from its nature, is one that must be continuously dealt with." Check out the smoky photo below of the old Vauxhall building from January, 1926, that used to be roughly where the Estes Kefauver building is now on Broadway.

As coal was a continued resource throughout the early 20th century, the task of the commission was then to just "reduce" or "abate" the released smoke in the air, if not completely eliminate. According to that same article, most citizens didn't think there would be an easy cure.

However, in order to get the ordinance passed and to help educate the public on the importance of the work, a publicity campaign was carried out for weeks throughout the city. In the images included in the flyers posted around the city, they showed pictures of how other cities had adopted a similar ordinance and were carrying it out.

The initial ordinance established was boasted upon quite well in the article, calling it "...one of the best smoke ordinances they [the committee] had seen."

A Few Details from the 1926 Ordinance

Here's a little bit about what the commission was and what their duties consisted of:

The Commission operated under the Board of Public Works and elected a mechanical engineer to essentially run the show. That person was "qualified by technical training and experience in the theory and practice of the construction of steam boilers and furnaces, and also in the theory and practice of smoke abatement and prevention." In 1930, apparently it was decided that the job was too much for one man, so they added a new part to the ordinance that created an Asst. Smoke Inspector position, Assistant to the Regional Manager, if you will ;)

- The commission consisted of seven members, who served without remuneration (getting paid) but instead acted as advisers to the Board of Public Works and the Smoke Inspector.

- The salary of the Smoke Inspector? "...not less than $3,000 nor more than $3,600 per annum (per year)". Roughly between $43,500 and $52,300 today. See the letter below from 1936, when the Smoke Inspector at that time requested a raise.

- The Assistant's salary? "...not less than $2,100 nor more than $2,400 per annum." Roughly between $30,000 and $34,500 today.

- In addition to the 2 inspectors and the commission, the ordinance also stated that the city's police department should also provide their assistance, by reporting any violations of the laws to their superiors.

In an attempt to help "abate" the amount of smoke produced in the city, one of the sections in the ordinance specified that "no new plants nor any reconstruction of old plants for producing power and heat, or either or them, nor any new chimney connected with a steam plant, shall be erected or maintained in the city until plans and specifications of the same have been filed in the office and approved by the Smoke Inspector and a permit issued by him for such erections, reconstruction, or maintenance..."

Another part of the ordinance that further enhanced the power of prevention for smoke regulation was stating that no owner or otherwise "shall alter or repair any chimney, or any old furnace or device, which alteration, change or installation shall affect the method of efficiency or preventing smoke" - without first submitting plans to the Inspector and of course, obtaining a permit.

Section 17 of the ordinance spells out what is considered a nuisance:

"The emission of dense smoke from any smokestack or chimney used in connection with any stationary steam boiler, locomotive, or furnace of any description, within the corporate limits of the city of Nashville (excepting for a period of 6 minutes in any one hour during which the fire box or fire boxes are being cleaned out and new fire or fires being built therein), in any apartment house, office building, hotel, theater, place of public amusement, school building, institution, locomotive, steamboat, or any other structure, or in any building used as a factory, or for any purpose of trade, or for any other purpose whatever, except as a private residence, shall be deemed, and is hereby declared to be, a public nuisance...

Any person in violation of this ordinance was fined "not less than five dollars nor more than twenty-five dollars for each offense".

The mention of burning only "coke or anthracite coal" is mentioned many times in the part providing specifications for heating (meaning capacity, pressure, etc.) Coke is defined by the Commission as "the residue left from coal after gases, oils, and tars have been removed at the gas works or coke oven." On the other hand, Anthracite is the least plentiful form of coal in the country (and world too most likely), but appears to be the best option for clean burning. According to Merriam-Webster dictionary, Anthracite is "a hard, natural coal of high luster differing from bituminous coal in containing little volatile matter and in burning very cleanly."

The definition of "dense smoke" according to the ordinance, is smoke that's equal or greater density than no. 2 on the Ringelmann Smoke Chart, which was adopted as the official standard for the City of Nashville. Check out the chart below.

The city's commitment to the task of helping alleviate the nuisance of smoke was quite thorough, based on other documents I've found in our collection; namely "The Smoke Nuisance and its Abatement" packet for citizens, business workers, and anyone else that used furnaces or boilers for heating in the city. The photo below is simply the start of the little notebook; it gets quite detailed.

And lastly, a few of the articles of equipment used or recommended by the commission included:

- Stokers (underfeed is the specific name), which were expensive and best for smaller boilers, but were apparently the best option because they eliminated smoke almost 100% (I can't explain what they were though cause I have no idea), and these reports are not exactly in layman's terms. What I can quote from the reports (from the 1926-27 report specifically) is this: "These stoker installations are, without a doubt, one of the brightest spots in Smoke Abatement as the elimination of smoke for the benefit of the City is so near perfect and the savings for the benefit of the owner are so pronounced that it is a case where everybody is a big winner."

- Down Draft Boilers were the next best option. According to the same report, these boilers were the nearest smokeless of any type of hand-fired boiler. It was also potentially referred to as an inverted underfeed stoker. They were also an efficient type of equipment for combustion of bituminous coal. At the time of this report (1926-27), the city had about 175 installations of these boilers.

- Air Blocks and Air Jets were a cheaper option over stokers because they could still stop smoke, but they're also listed in the report as not being the greatest economical investment. They only cost about $10-80 at that time (which still seems expensive for the 1920's), whereas stokers evidently cost around $2,000/a piece. Again, no clue what these things were or how they operated.

In conclusion, did the Commission make a difference?

I'd say definitely, albeit it might've taken a few decades to notice the difference. But based on the reports we have in the collection, things improved gradually over the several-month timespans in which most of the reports were written.

I skipped to the report from February 1st, 1929 through April 30, 1929 though, to try to wrap this blog post up as well as picking a 90-year anniversary report (well 90+). In the opening summary from the Smoke Inspector, George C. Fisher, he says:

"If Smoke Abatement had not been in force, during the last three years during which there has been considerable building of new plants and renovating of old ones, it would be difficult to picture the lamentable condition of the smoke problem and the great expense that would be entailed in making things right. Unsatisfactory and uneconomical equipment has been, to a great extent, banished from the City. The value of Smoke Abatement is accumulative to a large degree."

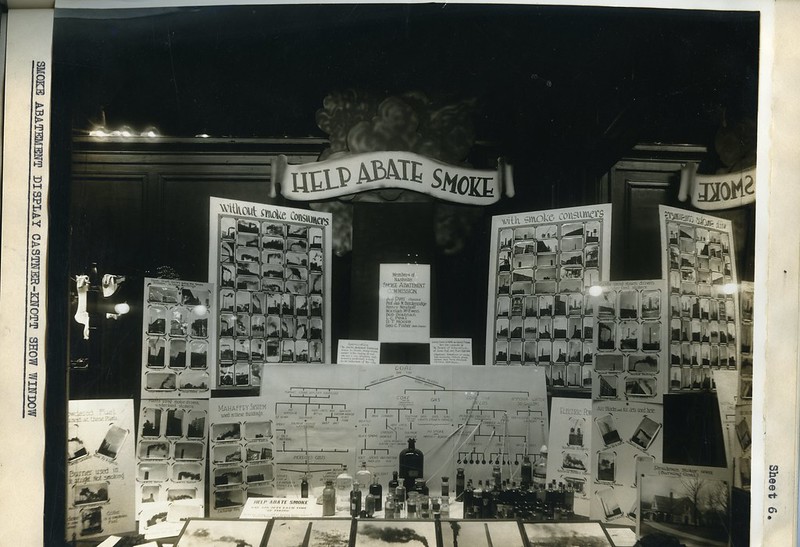

He goes on to talk in specifics about the Tennessee Power Company spending several thousands of dollars to help abate the amount of ash they put in the air. The trains and railroads in the city were doing better. The word about the work of the Smoke Abatement Department was being spread more thoroughly throughout the city, including having a booth set up at the Nashville Pure Food and Better Homes Show (see photo where they had a blackened lung in a jar!). More and more news articles were being printed with education about smoke abatement. The list goes on and on, but I now conclude with pictures!

If you'd like to see more photos from the reports, check out the slideshow here...

'Til next time,

Sarah